On Rediscovery, Lost Ancestry, and the Poetics of Myth and Meditation

A Conversation with Stephanie Adams-Santos

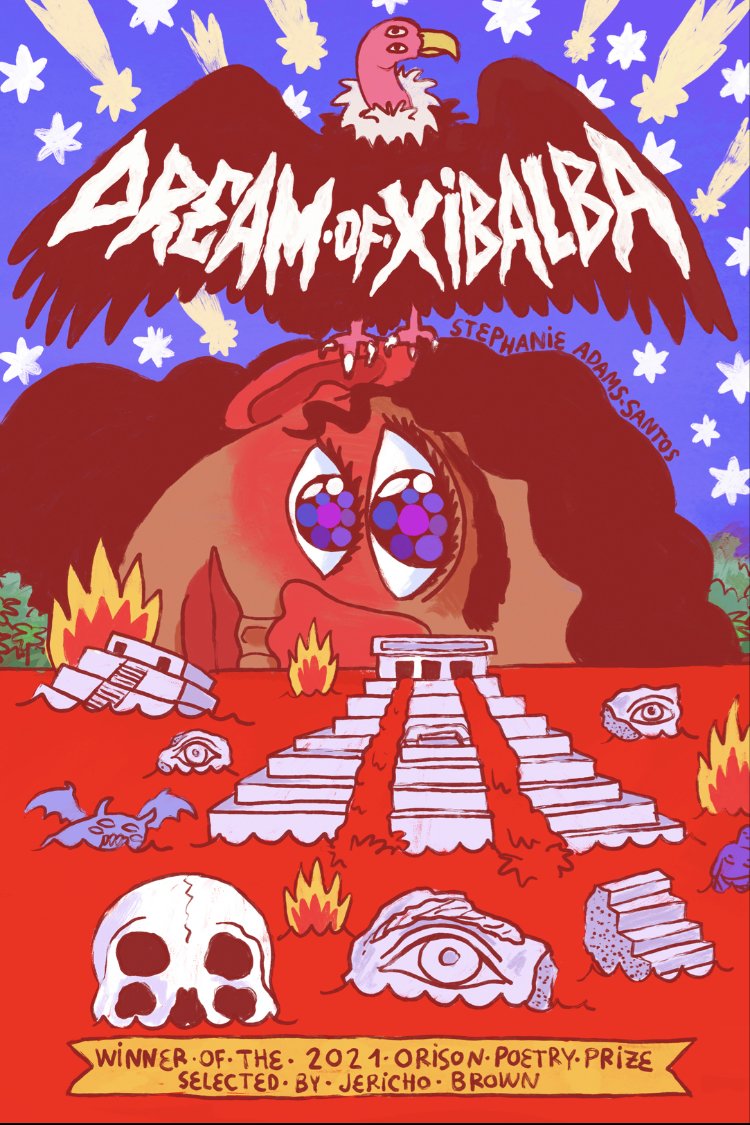

During my undergraduate studies, I took a course titled Native American Cultures North of Mexico, which was quite a misleading title since a large portion of our class was dedicated to the study of indigenous communities in Mexico and Central America. That same semester, I took an Anthropological Genetics course, and through one of our labs, I discovered that my mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)—which is usually inherited by offspring exclusively from their mother—hailed from the Oaxaca region of Mexico. Both courses combined added a historical and social perspective to the understanding of my ancestry, but they also complicated what I thought I knew about my identity. While growing up in the U.S.-Mexican border might have immersed me in two cultures, I was nevertheless caught between two worlds that were, strangely enough, both indifferent and welcoming. Throughout the course of my interview with Stephanie Adams-Santos, I thought about what her newest poetry collection Dream of Xibalba (Orison Books, 2023) would have meant to me during my college years, what perspectives it would have illuminated, and how it would have given me the confidence to accept that there are no easy answers when it comes to one’s identity. Part of knowing who you are is the journey of discovering your past, and as Adams-Santos’ speaker indicates early in the collection, even when you are “stuck in the world, / …your blood remains both here and there.”

I sat with Stephanie to discuss the origins of her collection, the differences in writing poetry and scripts, the influence of the band Tool, and what conversations she hopes her work has with her community and ancestors.

Esteban Rodriguez: Stephanie, thank you immensely for your time. I wanted to start with the end of section three in your collection, specifically the following lines on language, which hit close to home for me:

You can speak a little bit

of Spanish,But a lost language

sits on your tongue.A toad

the weight of stone.Black and green from the river.

Fulgent, the perfume

of its flesh.If you speak now

you’ll lisp, you’ll hiss.

Stephanie Adams-Santos: I’m so glad to know this one hit home for you. My relationship with Spanish is so painful and tender and complicated. I understand it, I am at home in its presence, it’s the music of my oldest memories. But my lack of fluency makes me feel like I’m alien to a vital part of myself. Language holds culture in such a living way. It’s woven with memory and belief and experience. Not being fluent in Spanish feels like not having arms but remembering the feeling of arms, or having phantom limbs that I can only move in my head. When I try to speak and my tongue betrays me, it’s so painfully frustrating — yet when I hear it spoken around me, I’m home, I feel my belonging in it. Language can be a source of belonging and alienation at the same time. That has been important for me to consider and accept in myself — that sometimes we can just let our broken pieces have their own life, their own story.

ER: Dreams of Xibalba is a journey centered on history, ancestry, the uncertainty of the past and present, and the cultural significance of personhood one must examine in order to arrive at a greater meaning, purpose, and truth. Did writing this collection lead to a discovery of aspects of your life and ancestry that weren’t as evident to you before you began?

SAS: Thank you so much for offering this reflection. “The cultural significance of personhood” and “the uncertainty of past and present” resonate very deeply. You’ve touched right at the crux of it. It’s so hard to know who we are. What we are. It’s the journey we all are on. We have to piece ourselves together from shifting truths, half-told stories, fragments, shards and shadows and absences. There are always missing pieces, blind spots, mute presences. There are always ghosts, whispers, lost languages. Multiple timelines of Being converge inside of us. The past is alive in us. The future is alive in us. I wanted to sit with the uncertainty, the unknowing, the incoherent pieces — and just let it all emerge. Like scrying in my own blood to see what’s there.

*

My maternal grandmother shaped the traditions of our family in the most cellular way. She was my soul’s root — she shaped my being, and gave me meaning in ways that bypassed my own knowing or conscious thought. She was my living history. My living library, my codex. I didn’t need to know my lineage because it was alive in all my senses when I was in her presence. Just being in our family home in Guatemala, I could live in that history through the smells, the sounds, the dust, the comal, my gramita’s hands and arms when she made fresh masa on the mortar stone. I could hear the traces of our Mam roots in certain words she used, or in the way she prayed, in the lilt of her voice when she told stories, in her vocabulary. When she died, and I lost access to not just her but our family home, it felt like a piece of my soul was locked away in a room I would never enter again.

A month after her death, I quit my job and embarked on an unknown path into screenwriting. Living in L.A., lonely and estranged, I would often lie sleepless at night listening to coyotes or fat green locusts hitting against the glass. I would hear sirens, helicopters, and far too often — blood-curdling screams. At night I became a raw organ of sensation, and the whole world tunneled into me. Trump was president. Children were being separated from their families at the border. The West Coast was on fire. I was away from my partner and my dogs. My grandmother was no longer accessible to me in the tangible world. Everything was uncertain. I was a cloud without a center. I didn’t feel real or connected to anything. I was a cut stem. My writing felt as fragmentary and incomplete as I did. I didn’t know if I had anything to say beyond some kind of scream, or some kind of question I didn’t even have the words for. That’s how Dream of Xibalba began. A collection of fragments that felt like nothing. But as I started to put the fragments side by side, I felt something tangible there. I had the notion that fragmentation itself could be something powerful. Something true. Not just for the book, but for my spirit (those are intertwined). I let everything blend together — the past, the present, memories, stories, musings — however incomplete or anachronistic. I let the ghosts in myself speak. I let sense-memory guide me. I let the fragments mingle together and become the body of the book. That was the major discovery for me — that we don’t need wholeness or healing or perfect memory or foresight or knowledge or facts or even comprehension. It’s okay to just be. Incomplete and without resolution. “We make an unsubstantial territory” (Woolf). Our center can be empty. We can live with our woundedness. We can make a home for the Unknown inside of ourselves. This gave me courage, and a sense of rootedness in the world that I didn’t know was possible.

ER: Can you speak further about Xibalba for readers not familiar with Mayan mythology? What drew you toward rendering this world in such a poetic manner?

SAS: The past few years have felt like inescapable fear and anxiety. We are going through something of a collective death. A collective underworld journey. Our mythic underworlds create a living container for the collective grief, sorrow, pain, fragmentation and loss that we experience. It’s important to have these mirrors to reflect what’s inside of ourselves. As much as I honor the importance of joy, I also never want to look away or diminish the significance of whatever suffering is moving through me and/or the collective.

Xibalba is the name of the Mayan underworld — “place of fright.” The terrifying lords there are responsible for all the forms of mortal suffering that exist in the world. As horrific as Xibalba is — rivers of pus, scorpions, and blood — its imaginative rendering is exquisitely creative and fertile and quite playful. In the Popol Vuh creation myth, a daughter of one of the lords of Xibalba, Xquic, gives birth to twins after a decapitated head spits in her hand. Her sons become heroes, going on to conquer the underworld journey that their dead fathers could not. This story has whispers in it for me about the ways intergenerational trauma, loss, memory, and fragmentation carry into our present journeys.

Xibalba came alive for me in the writing — not as a distant mythological concept or metaphor, but as a real place — fragmented and alive in my being. My goal wasn’t to conquer it or simply pass through it and emerge on the other side. Actually, a sort of inverse underworld journey started to manifest— an underworld daughter, a lost daughter of hell, finding her way in the world above. The mythos itself is fragmented and shifting. Like a dream.

I chose the title “Dream of Xibalba” as a way of inviting the Unconscious into story — that great cauldron of ourselves, where past and present, pain and joy, ancestor and future self coexist in imperfect wholeness. The dream we live in.

ER: The book is divided into 12 sections, and throughout, there are surreal narratives that almost read like dreams. It’s hard to not to go back and reread and reinterpret every part, especially when the speaker is at the center of uncertain surroundings, such as the section below:

At dinner you find a slick gray stone

floating in your soup,

the heart of a hen

en el caldo, un espejo.

You turn, not wanting to see

a woman in whitewho crosses the courtyard, hollow-eyed,

mumbling her ballad of the machete—mi marido me quitó las manos

mi marido me quitó la cabezaThe pain of her body trails behind her

in the shape of a dog.

How did you go about manifesting surrealism on the page? Were there literary and/or non-literary influences when you put pen to paper?

SAS: I remember being very young in Guatemala and finding a chicken heart in my soup. I was haunted by two things: the particular hue of gray felt strangely taboo, and the sudden nearness of that creature’s death. Another time, I saw a woman crossing the courtyard late at night and was very sure it was La Llorona herself. Nobody would wake up, and I felt a kind of existential dread in having to hold that experience on my own. Another time, my gramita told me about a neighbor (or cousin?) who was murdered by her husband with a machete, and for weeks afterward she would hear the moaning of her ghost. These three memories came to live together in this fragment, speaking to each other in the way dreams do, forming their own surreal dialogue about death and the body.

Dreams and unconscious life are very important to me. I always adored the Wallace Stevens quote “the poet is the priest of the invisible” because it speaks to the power and presence of forces and dynamics that shape us beneath or beyond the veil of consciousness. When we dream, our body reveals some of its inner drama. Our imagination lives in the body.

To me, the inner world is quite literal. Our memories and experiences (personal and ancestral and primordial) are imprinted in the cellular landscapes of our bodies. Surrealism feels very “real” to me because it seems to speak directly to an inner experience, giving shape to the dramas and mythos and fantastic pictures that literally shape our inner life, our dreams, and reflect our experience of being alive in the most visceral and imaginative way.

I’m deeply indebted to the surrealism of poets like Xavier Villarutia, Alejandra Pizarnik, Eunice Odio, Marosa Di Giorgio and Ferenc Juhasz — their work spoke deeply to me while I was writing Dream of Xibalba. Their imagery could open doorways for me when I felt stuck, or shine strange light into familiar corners I thought I knew. Toni Morrison’s Beloved has also been a very important work to me in considering the ways in which the the past lives in the present, explored through the surreal haunting/wounding at its center. Other surrealists who have heavily inspired me over the years: Odilon Redon, Leonora Carrington, Rene Magritte, Frida Kahlo, and Giorgio de Chirico.

ER: How has being a Tarot reader influenced your writing? What beyond literature and art inspires you?

SAS: For me, the practice of Tarot creates a powerful container in which my unconscious, intuitive, and embodied knowledge can playfully emerge. It invites mystery and larger connectedness through spiritual play. I feel my inner child at work when I engage in these types of rituals — Tarot, altar-tending, hechizos/spellcrafting, prayer. I don’t know how Tarot has influenced my writing directly, but it’s one of the many tools and processes that I use to stay open and in touch with Mystery, which is crucial to my creativity and fluidity as a whole. Tarot and poetry have a lot in common for me — the power of the image, the fecundity of the symbol. A good Tarot deck, like a good poem, comes alive each time you engage with it. It can be precise in its particulars but never holds its meaning by the throat. Its living archetypes complete themselves in the reader. It shows you new things with each reading. It changes as you change. I look for magic wherever I find myself. I’m an animist — I believe there is spirit in all things. I want to be ever-opening to that. I’m inspired by experiences and activities that offer awe or deep rest, connection, or joy. I’m inspired by old growth forests and insects and creatures of all kinds. I love movies and especially animation. I’m forever stirred by the lush, magical worlds of Miyazaki/Studio Ghibli. I’m inspired by my dogs and their intense, emotional attunement to the world through all their senses. I’m inspired by spaces that invite physical and mental comfort. A lush bed with lots of pillows, for example. Or a cabin in the snow with a fireplace. As much as I can I like to get out of my head and drop down into the other parts of my physical being. I like non-lap swimming in warm water pools. I love making soups without recipes. Art and crafting is a great source of inner motion for me. Painting, drawing… And music! Music has such power. I sometimes like to play the most serene cello or a Ghibli soundtrack or a swelling, emotional movie soundtrack — other times I play Tool or metal without vocals, or sometimes just simple white noise… whatever keeps things moving.

ER: I love that you mention Tool, a band that constantly inspires me. Listening to them, and thinking about their work, I can’t help but think of the process of creating art. For Tool, there was a 13 year gap between 10,000 Days and Fear Inoculum, which by creative standards is quite long (you will more than likely see bands put out an album every three to five years). I’ve read in various interviews that their creative process was slow because they didn’t feel the need to rush the composition of songs. At what pace do you approach a poem? A book? Is there a struggle between urgency and patience?

SAS: I love everything about this question, and am a little giddy to know that you’re a Toolhead too. Tool is so, so epic. Emotionally and spiritually. The patience that you talk about is present in the songs themselves, as well. The slow swells toward incredible, cathartic releases of energy. They are a huge inspiration to me, a lifelong companion. Thank you for bringing them into the conversation. I’m a very slow writer. I liken my thinking-brain to a swamp. Maybe a bog, more like. Pickling thoughts and forms until they become something different. It’s so slow sometimes I don’t even register that anything is happening. I tend to judge myself pretty hard for this pace of work, so I appreciate the reminder of Tool and their epically-slow pace.

In my screenwriting work, lots of things have to happen on strict, fast deadlines — and even if no deadline is imposed, there’s a sense of timeliness, an urgency.

But my poetry answers to no deadlines. I let poems evolve as long as they need to. Even if that takes a year. I know many poets write with books in mind, but I tend to wait until a shape starts to suggest itself. I feel like the idea of a “project” imposes something on the poems that feels too external or lifeless. I try to keep them close and unconscious and umbilically connected for as long as possible — and once they have some blood of their own, shape of their own, then I can start to bring consciousness and intent. For Dream of Xibalba, I was surprised to discover that my scribblings and fragments had formed themselves into a booklike thing. For years I was just writing, out of some blind inner need, meanwhile wondering what my next book could be — not even realizing I was writing it. Once I put the fragments together, I saw the shape taking form, and it showed me what it wanted to be. Poetry is very dreamlike – it teaches me about myself, shows me what’s moving inside and trying to rise to the surface. I enjoy that mysterious process of discovery that I have no mastery or control over. Even if I wanted to speed it up or take a more conscious approach, I don’t think I’de be capable. I’m a total bog-person.

ER: Just because we are on the topic of Tool, I have to ask, do you have a favorite album? Song?

SAS: The work by Tool that I come back to the most often is the song cycle of Parabol and Parabola on the 2001 album Lateralus. Both songs have virtually the same lyrics, but the experience of each one is wholly different. And the experience of moving from Parabol to Parabola is profoundly stirring and cathartic. In the first song (Parabol) there is a mournfulness and introversion, and in the second song (Parabola) there is an exuberant extroversion. I think it’s endlessly brilliant to capture that duality and potential for transformation between the poles of existence.

I think it’s worth sharing the lyrics because they unexpectedly fit quite well with themes that surfaced for me in “Dream of Xibalba”:

This one, this form I hold now

Embracing you, this reality here

This one, this form I hold now, so

Wide eyed and hopeful

Wide eyed and hopefully wild

We barely remember what came before this precious moment

Choosing to be here right now

Hold on, stay inside

This body, holding me

Reminding me that I am not alone in

This body, makes me feel eternal

All this pain is an illusion

ER: The question and your response brought to mind the start of the eleventh section, and the following lines:

Most days you move like a ship.

Blood over the desert.

The rolls of your back

slope like the dunes themselves.When you lie down

the softness startles you,

your nakedness conversing with the elements.

What conversation do you hope Dream of Xibalba is having with your ancestors? With your peers, friends, family?

SAS: When I wrote that piece, I think I was unconsciously exploring how our bodies are a part of nature, even if it doesn't feel that way. There can be sudden softness, sudden discovery, in just simple moments of being. We don't always need to comprehend or analyze or decipher our identities, our fractured lineages; sometimes it's enough to just feel the cellular wholeness and unbroken chain of life that exists in the mystery of what we are and what we are a part of. We are intimately entwined with the material world and there is a sense of unity that can be experienced through the simple act of being present in our bodies. There are moments of divine connection that carry their own fullness.

I really love this self reflection by Toni Morrison: “Everything I've ever done, in the writing world, has been to expand articulation, rather than to close it.”

In my own poetry, I aim to speak from my most primal place of utterance, to “expand articulation” in my blind gropings toward the forms and motions of inner experience.

In a way, Dream of Xibalba is a lyric altar to my ancestors. I hope that they, who live continuously within me, can find utterance through my corporeal existence. May we deepen our conversation forever.

And for my friends, my family, my readers, I hope this text can be an invitation to hold such an altar within yourself, that in the empty spaces of your own loss and fragmentation and seeking, you might find the silence and mystery and beauty that holds it all together.