In the Belly of the Unknown

Peter Wayne Moe’s Touching This Leviathan has many missions, all of which involve a search for the unknown. On the surface, the quest for the unknown might seem like an antiquated or problematic pursuit, drawing our attention away from the morally pressing issues of our more immediate realities. But part of Leviathan’s brilliance is how Moe makes this timeless quest urgent for a contemporary audience. For some, the unknown might signify a conceptual space that describes an elusive, undefinable, or impenetrable absence. Yet the irony of absence is that compels us to discover something substantive within it. It’s counterintuitive, but the vacancy which lies at the heart of absence also suggests futurity, possibility, and deferral. Absence always intimates what could exist. The unknown, then, is more than what it appears to be in that it marks something beyond itself, a reality whose existence is both conditional and contingent upon the success of our efforts to discover it.

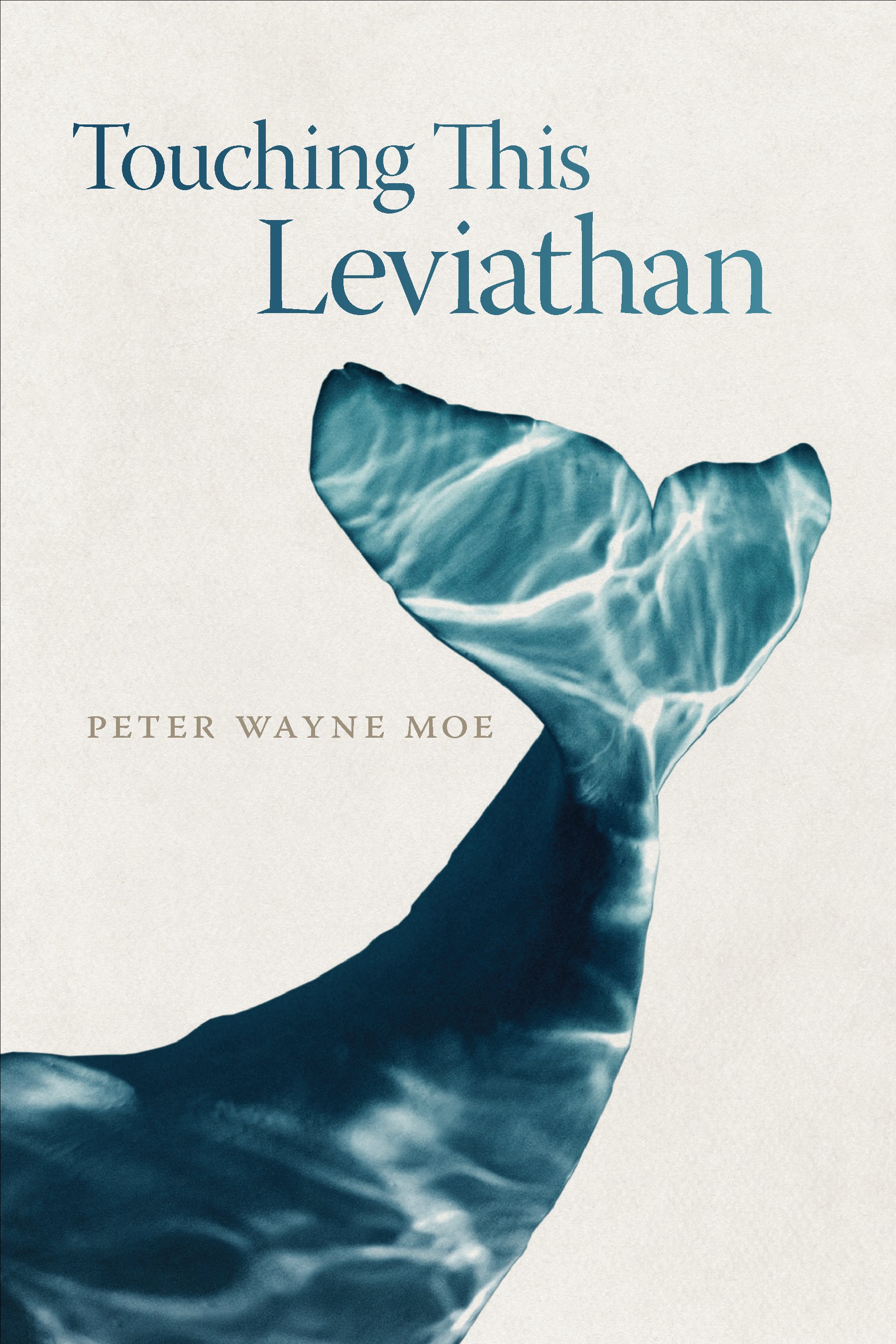

Investigating the unknown is a bold undertaking—one that tends to demand heroism from those who embark on this special journey, at least traditionally—and Moe seems keenly aware of this as he imagines himself writing alongside literary and biblical giants like Job and Melville’s Moby Dick. I remember reading both of these texts and feeling somewhat overwhelmed by the grandiosity and impossibility of it all, but in Leviathan I could feel the weight of the unknown without being burdened by its profundity. How refreshing to encounter this ancient theme in the everyday and the ordinary facets of Moe’s life. Leviathan reckons with topics like faith, fatherhood, science, and of course whales. The book is both memoir and meditation, an act of documentation and profound reflection. As a result, a sense of sacredness permeates the writing, so that even those pages which are filled with biological and statistical data are felt to be intrinsically spiritual but also vital to comprehending the larger mystery that Moe is committed to both finding and describing.

Touching This Leviathan by Peter Wayne Moe. OSU Press, 2021. 166 pages. $19.95.

Formally, Moe’s interdisciplinary approach creates cohesion between genres which are typically assumed to be at odds with one another. Science, literature, and scripture are treated as equals in the book’s unfolding dialogue with the unknown. Moe’s goal is not to establish any sort of absolute truth or epistemic authority, but rather to bring intellectual legacies of different histories and cultural traditions into sacred communion. Both science and faith are explored as equally valid pathways of knowledge that are able to bring his reader closer to a kind of wisdom which reconciles ideological opposites—perhaps transcending them altogether. Leviathan is about whales in a literal sense, to be sure. It is full of fascinating historical and biological facts about this intriguing species which work to inspire feelings of awe and wonder for this majestic mammal. For me, those feelings were extended toward nature and ecology more generally; without question, one of the book’s greatest strengths is how it fosters a deep sense of appreciation not only for whales but also for the environment.

Melville’s Moby Dick is an ongoing conservation partner in Leviathan not only in those instances where Moe quotes Melville directly, but in the very fact of writing about whales in the first place. Moe manages to avoid the posture of dissection and that objectifying gaze which characterizes the intellectual culture of both Christianity and Western science. In fact, the avoidance of order, tidy conclusions, and carefully prescribed approaches to inquiry is a deliberate choice for Moe. He explains that only “disorderliness” can bring us closer to what cannot be fully known or defined:

I take a cue from Melville: “There are some enterprises in which a careful disorderliness is the true method.” I employ this careful disorderliness, my project defined by gathering extracts, by curating an archive. Key to the method, then, are section breaks each chapter. These jumps are an effort to pull from as many places as possible, places perhaps not the most obvious when trying to write the whale.

Moe knows that this careful disorderliness requires his audience to have a certain level of faith in his effort to “write the whale” he doesn’t yet understand. Quoting Verlyn Klinkenborg, he tries to imagine a reader he can trust, one who will commit to the ongoing process of knowing. For me, this created an experience of reading in which I felt the equivalent of being carried along by the gentle motion of a current, or left floating atop the surface of an ocean of both memory and knowledge. Far from feeling insecure or unnerved, I knew that the field of Moe’s inquiry was open, vast, and ripe with creative and spiritual possibility.

The Christian mystics considered the unknown to be an epistemological end in itself. This way of knowing—or not-knowing—is a distinct form of knowledge which relies on a commitment to intellectual vacancy, to emptying one’s mind of what they think they already know. Continuing his description of the reading experience, Moe explains that he hopes his readers will piece together the many parts of a greater whole that has yet to be discovered as both move “into the belly of the whale.” As one reviewer noted, this book makes a number of paradoxical moves that enact a state of mystery even while Moe searches for it. It is an obvious work of spirituality that resists easy theological conclusions; it relies on science yet confesses the bankruptcy of a strictly empirical approach:

Eight months after the flensing I take my son to his first Ash Wednesday service. Purple paraments hang in a dark and silent sanctuary, candles lit. I say the words of the liturgy, and I hold my son, my long-awaited son for whom we, in our infertility, mourned and in whom we, through the mysteries of pregnancy, now rejoice. I walk down the aisle, my son asleep in my arms, his head resting on my shoulder. “From dust you came and to dust you shall return,” the priest says, dipping his thumb in the ash and again intones the words, marking my son… I do not like remembering my own mortality, let alone his. The rain falls on us all, but I think of these bones I have, bones buried deep beneath the earth. Grass grows there again, and it’s the deepest green I’ve ever seen.

By the end of the book, the figure of the whale is made fully visible as Moe offers one last reflection on its flensed body. He shares the lessons he’s learned along his journey with his trusted reader, culminating in this final moment of gratitude:

I now know my naïveté. I’d thought we would just slice into the whale, grab a bone, and pull it out. The whale has taught me—in the most visceral way possible—that bones are attached to everything. They’re clothed with muscles, tendons, ligaments, and sinews, and all this must be cut from bone and body. And try as I might, I just can’t muster the same enthusiasm as these biologists. It’s all I can do to keep working. Throughout the day vomit comes up my throat and then returns back again. When it does I pause, sit up, and breathe the sea air. I’m thankful for the wind.

It’s a fascinating passage in when the total exposure of the whale’s dismembered corpse demonstrates naïveté. It’s as if the pursuit of the unknown has proven itself to be more of an alluring temptation than anything else. Moe does not technically succeed in demystifying the whale even though he does approach it both literally and symbolically. But maybe that’s the revelation, the one both Ishmael and Job came to as well. Maybe linguistic knowledge and historical knowledge and scientific knowledge are ultimately inadequate approaches to understanding, or at least approaches with limitations. Maybe negative theology is right. Still, Leviathan seems to believe that the mere effort to apprehend something as elusive as the unknown has value, and resists retreating into the severe conclusion that we can’t know anything at all. In the end, that’s something worth knowing.