Can We Remind Ourselves That We Are Wild?

An Interview with Sun Yung Shin

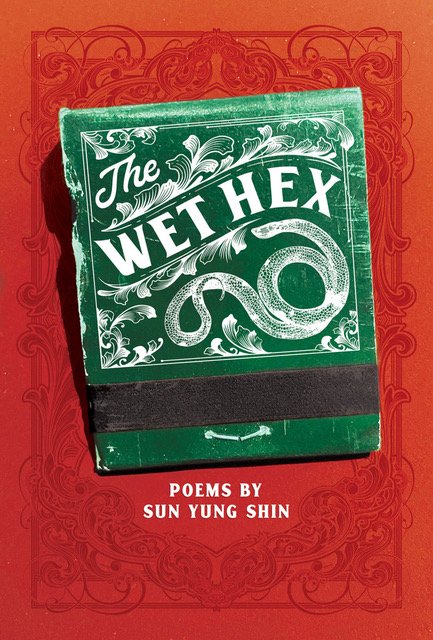

Sun Yung Shin’s first collection of poetry, Skirt Full of Black, was one of the first collections of poetry I read by a Korean American poet as an undergraduate, and her poetry, as well as her vibrant and life-giving community work, has been a guiding influence in my life ever since. In addition to her three collections of poetry, most recently, The Wet Hex, Shin is also the editor of several anthologies and the author of two children’s books. She is also an educator, jewelry artist, and bodywork practitioner, as well as co-director of Poetry Asylum, a Twin-Cities based organization that “creates diverse platforms outside privileged spaces to bring poetry to traditionally marginalized communities through open dialogue, innovation, collaboration & advocacy.”

Our conversation was wide-ranging, touching on relationships to time, mortality, and descent, the complicated relationships among language, power, and ritual, and the potential of myth to help heal wounds. You can read more about Sun Yung Shin’s work here.

Leah Silveus: Could you tell me a little bit about your process of writing The Wet Hex? Was there a certain place or setting you did most of your writing? Out of what elements/experiences did it emerge? Was there a first poem or a first line?

Sun Yung Shin: I started the book writing process by thinking about a few things: the death of my father in February of 2017, mass extinctions on our planet, and the racial politics of evolution science.

There is no certain place or setting in which I did most of my writing. I have no routine, which I don’t necessarily recommend!

I don’t remember what the first poem was, but it might have been the poem about the Dodo. There were some poems about my father that I wrote before he died that were in the manuscript at first but then didn’t seem to fit so were taken out later.

Leah: I’m interested in the relationship between this book and your most recent book, Unbearable Splendor. Unbearable Splendor dealt with, among other things, the notion of guest and host, exile and homecoming. The Wet Hex also seems to invoke a motion of departure as well—this time into the underworld. How do you see the relationship/movement/journey/pathway between your last book and this one?

Sun Yung: Thank you for this thoughtful question. I see The Wet Hex as reflecting more of my concerns about climate change and ideas of descent, both genetic descent and descent into the underworld. The first title for the book was Utopias of Descent and I was trying to work elements of Thomas More’s Utopia into it, into thinking about human constructions of utopia, paradise, and other kinds of -topias/places. Our imaginaries, our relationships to other animals and life forms, and what kinds of thinking or feeling might poems be able to make space for.

My father was alive when Unbearable Splendor came out in 2016, and less than a year later, he would no longer be alive, so my relationship with him changed and that informed the book, and my relationship to time and my own mortality.

Leah: We have spoken before about the ways that our religious upbringings have shaped or informed our poetics. In our conversation about Arabilis for Hyphen magazine, you commented that, “I was raised Roman Catholic and it was very much part of my adoptive family’s extended families’ cultures in terms of being Irish and Polish. We went to Mass every Sunday morning at 8:15 and sat in the same pew. I feel like I’m constantly thinking about it in my poetry and poetics but have always felt like kind of an oddball, both under the broader Asian American poetry umbrella and in the world of experimental poetry.” I also recall you speaking on an AWP panel called “Poetry as Spell-Casting” about being introduced to the magic of language through Catholic liturgy. In The Wet Hex, you also draw on Korean Shamanistic traditions. Can you talk about the role of the religious/ritual in this book and in shaping your poetics?

Sun Yung: I’ve always been fascinated by religion and ritual, especially in regard to the choices people make in terms of authority and obedience. One of my dominant experiences of the Roman Catholic church is one of patriarchy and gender binaries, and one of things that fascinates me about Korean shamanism is perhaps first and foremost the fact of female shamans.

Leah: I’ve been interested in the diverse range of texts that you invoke, reimagine, and subvert in your recent books. The bible, Dante’s Inferno along with Greek and Korean myths are just a few examples among many. Can you tell me a little bit about what draws you to these narratives and about the role that these retellings or imaginings play in your poetics?

Sun Yung: I read so much mythology as a kid, especially Norse and Greek mythology, because that’s what was in my school’s library, as I recall, and I loved how human the gods were in comparison to the Christian god. I loved how Zeus and Odin and Hera and Freya were individuals, but immortal, and had supernatural powers, unlike the Holy Trinity, in which there was God, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit, and they were separate but also one. I also had a book of Korean stories, The Story Bag, and that was one of a few Korean artifacts or cultural mediums I had, so it had almost a supernatural presence for me. I think one role they play in my poetics is that they showed me how literature could provide a liberating space for thinking through what being human meant, aside from my family, school, government, and church. I also know that accessing and working with myths are a way for me to heal my wounds related to being an abandoned child and someone who will never know their origins or ancestors. So many heroes in myths are orphans and have to leave their homes or homelands to find meaning, purpose, and identity.

Leah: I love the array of formal modes you draw up on in your work. In addition to left-justified, lyrical poems, The Wet Hex also includes found text including excerpts from Columbus: The Four Voyages 1492–1504 and your personal Korean passport, along with a poem/drawing collaboration with Jinny Yu, and a form of partial erasure in “Whiteness: A Spell Thrown.” I think I also remember you showing a poem at the AWP panel in the form of a word search, which I loved. What is the importance of moving among these different forms to your poetics?

The Wet Hex by Sun Yung Shin. Coffee House Press (2022). 120 pp. $16.95

Sun Yung: I find them exciting, to work with language more as a material than as their abstracted meanings. I also think working with primary documents, working with the words of another person, especially one whose words have been so significant, whether Columbus or Melville, feels like a power play, a way as a woman to place myself as equal to the male voices of the past, that have been given so much more space than women of their time, and our time, let alone their whiteness(es), which is obviously foundational to their projects.

Working with my own documents such as my Korean passport is a way for me to fetishize them as if they were in a museum, and sometimes I think of poems as museum exhibits. By fetishizing them, I hope to show the Kafka-esque power of bureaucracy and also how the violence of borders needs language and paper in modern times. That poems and passports have a kind of equivalence is startling, I think. Anything that helps us wake up to our conditions, and (often dehumanizing) ways we are controlled, categorized, separated, designated, etc. seems important to me. We are not free to move about this planet, and the nations that enact those laws use language (and images, photographs) (and numbers) to identify and track people. When we let documents become more important than humanity, than compassion, then rationality, we are prisoners. This is a feature of literate, low-context societies. Poems, as artifacts of language, should talk back to these other artifacts of language (laws, identity documents, etc.) that constrain some of us to death and allow or mark others almost as free as birds to move across the planet.

Leah: The Wet Hex is so sonically rich. I love the work you do with rhymes and wordplay and the interrogation of the politics of language that rises out of that play. Could you tell me a little about the way you conceived of/envision the soundscape of this collection?

Sun Yung: Thank you! I love the musical potential of poems. One of my ongoing everyday pleasures is admiring slant rhymes in hip-hop lyrics. In this collection, the soundscape is important because they feel like poems in the dark, and in the dark, we may become more attuned to sound as sources of information. The seductive language of advertising copy, and its exploitation of sound, highlights for me how vulnerable we are to sound’s power, and how it can stun us into submission or give us fortitude, and just all around provide regulation to our central nervous systems, such as when we drum together, or sing together. This is also why ritual, especially en masse, can be so seductive, and of course, dangerous, bypassing or overwhelming our rational thought processes, our resistances to persuasion. Language is like a rattlesnake! We get hypnotized or at least distracted by the sound of the rattle so we don’t notice the fangs coming at us.

Leah: We have spoken before about our ambivalence about identifying as “adoptee poets.” For me, adoption has played a critical role in my sense of self and poetics, but I feel a bit of tension in identifying as an adoptee poet; maybe I am afraid that it will pigeonhole me or be too restrictive, or maybe it’s because while it’s one aspect of my poetics, it doesn’t encompass all I am trying to do as a poet. I was wondering about the way you see adoption informing your work, experientially or notionally. While you don’t always write about adoption explicitly, there seems to be like a sort of adoptee poetics in the ways that you deal with liminal space, belonging, relationships to languages, family, and the body. You also notably dedicate The Wet Hex to “those cast away.” Could you tell me about how you understand adoption/orphanhood/anything that family of things to have shaped your poetics?

Sun Yung: The condition of being adopted from South Korea to the United States, being abandoned and placed for a process by which I was sent permanently to the care of an unknown family of strangers on the other side of the world, without my consent of course, informs my work in almost a totalizing way.

I don’t call myself an adoptee poet aside from in certain adoptee spaces because most people don’t know what adoption means, or at least means to me, and because the propaganda around adoption is so longstanding, so stultifying, and so gaslighting, I prefer to leave the word out of my writing. It’s too charged and it is a distraction unless I have time to deconstruct it, which I do a little bit in an essay about the word “adoptee,” which I really kind of despise, in Unbearable Splendor.

I could write a whole book on how being adopted informs my poetics, but I’ll say that being a writer in English when I would have been a lifelong fluent speaker of Korean, informs my general approach to language as a construction. And I think in poetry I’m often trying to look closely at the seams and the tears and also the theatricality of language. What does a word mean versus what some authority tells us it means? I think of Orwell’s Animal Farm and other dystopian stories in which the powerful convince many of the subjugated that they are free when they are decidedly unfree. Language is a tool and technology and it can be applied anywhere the powerful want it, and my very former American name and the English language I think in, speak in, and write in, is evidence of that. It’s a tool of colonization, and it becomes embodied, and therefore is maybe impossible to be free of in this lifetime. Writing poetry is a way of externalizing some of the poison of a colonial language, not to poison others, but to reduce the harm it does to me, hopefully making me less likely to unskillfully harm others. Harm reduction. Making poems is formalizing language, controlling it in a way, making a tool. I want my poems to be useful, to make spaces that others can dwell in and find something useful in.

Leah: In addition to writing, editing, and teaching, you do so much, including co-directing the Poetry Asylum with Su Hwang. You are also trained in restorative justice and bodywork practices including Reiki and biodynamic craniosacral therapy, and you make a stunning array of jewelry. How do you find these different practices inform each other, if they do?

Sun Yung: Thank you! They feel like they come from the same thing, which is a deep desire to participate in collective healing, of wanting to be and feel more free. Can we be doing more to fulfill our potential as beings on this planet? Can we remind ourselves that we are wild? That we are animals? That we are mammals and are no better than any other life form, and in fact as Homo Sapiens, we are very very new in this particular form. That we have so much to learn from plants and animals and fungi and bacteria that have been here for billions and millions of years, with many of them being in their current form. In that way they are perfect in this world. We humans seem so deeply unperfect, or just deeply “junior” compared to these elders!

Leah: Is there a question that no one has asked you about The Wet Hex yet that you would like them to ask? What would it be and how would you answer?

Sun Yung: Maybe about the 19th century sublime? The Tate Museum says, “The theory of sublime art was put forward by Edmund Burke in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful published in 1757. He defined the sublime as an artistic effect productive of the strongest emotion the mind is capable of feeling. He wrote ‘whatever is in any sort terrible or is conversant about terrible objects or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime’.” Perhaps from being raised as a Catholic, the idea of artistic effect as terror speaks to me. That intersection of agony and ecstasy, and art as a way to transcend our mortal and temporal bindings in a way, seems like a form of freedom, a kind of touching of the infinite, the boundless, because who can say what the limits are of “the strongest emotion the mind is capable of feeling”? Emotions are signals, and it’s good for us to pay attention to them. What are they telling us about our potential as beings? Our oneness with the universe?

Leah Silvieus is the author of three poetry collections, most recently Arabilis (Sundress Publications 2019), and is the co-editor with Lee Herrick of The World I Leave You: An Anthology of Asian American Poets on Faith and Spirit (Orison Books 2020).