A Story About Madness

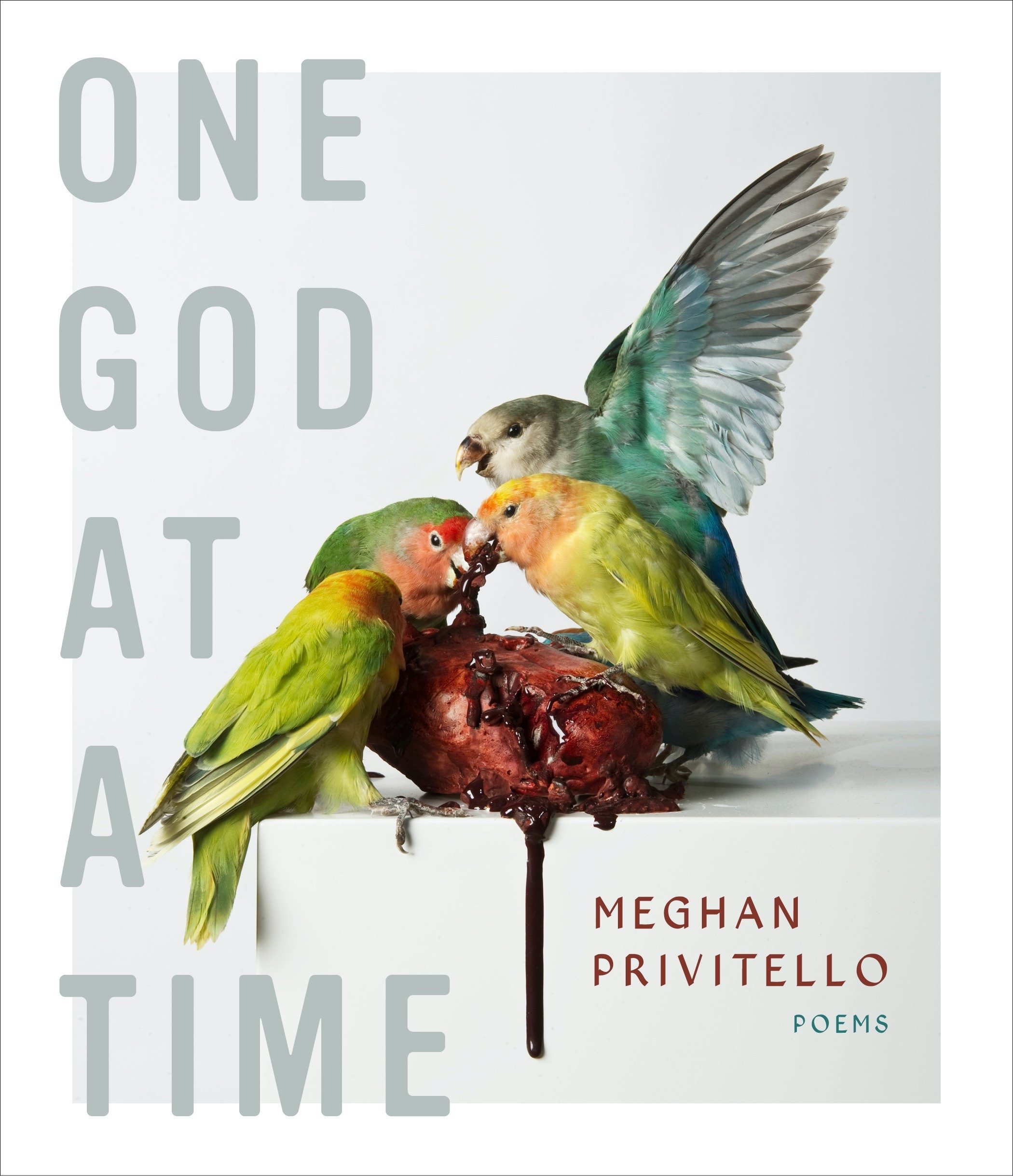

One God At A Time by Meghan Privitello. YesYes Books, 2020. 100 pages. $18.

“I am trying not to be a lunatic / in this strange, poached world,” Meghan Privitello writes in “Bad Tongues Said,” a poem that comes late in the collection, reading like a confirmation of what we’ve suspected all along. At the heart of One God At A Time, Privitello’s second full-length collection, is Hamlet’s famed proposition about madness: speaking to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in Act II, Hamlet says he is “but mad north-northwest. When the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.” On the surface, this describes his ability, in the right light, to sense danger—to tell a predator from prey. But the line has come to mean something greater about how we know reality—can we name one thing, and understand it, as separate from another? If not, we’re doomed.

Reading this book, you feel that this everything-is-everythingness is always, for the poet, a heartbeat away: the world is a jumble sale and God a shitty, looming presence in each trash article, right down to their sub-atomic particles, such as in “The Communion:”

Take into your mouth everything but

the beef of the other. Curtains, bird

nests, bridges, smoke, etc.

Or, again, in “Chromatic”:

God prayed for rooftops

and got the alphabet.

Houses were to come first.

Then umlauts. Then love.

These poems are a way of staying sane by naming the unaccountable, a fight to turn the ineffable, the unspeakable, concrete. Privitello must name, shape, and order every object—or, collectively, they threaten to become a leviathan. This is also a version of transcendence—everywhere on the page is Privitello’s terror and wonder at the abyss:

…Trace your ancestry back

to the sea bed. Begin your body from

no one. Watch God’s excitement as

he sees your meaningless figure… (“The Begetter”)

Claudia Cortese writes that, “Plath kills God, but Privitello goes further. She and God perform a power play.” I’m not in agreement that Plath kills God (I think immediately of her late poem “Mystic,” where God is ever-present), but it’s apt to note the influence. Like Plath, Privitello’s poems are high-stakes, and read like they’re written at a fever pitch, such as “Quiet Is My Souvenir,” with its rapid-fire moves from abortion to a father’s debilitating illness, to a masterful, oblique reference to paternal abuse:

…This is sounding

more like a plea than any revolutionary way of saying loneliness

it is what I would tell God if he ever broke

into my home and said Speak or be gone.

He has it coming to him, being another father

that once woke me in the night to say Pretend

I was never here. And he wasn’t. And he wasn’t.

Like Plath, Privitello is unafraid to tackle the gruesome, while also writing, from time to time, some very funny lines. The terrible is center stage, here, and any comfort one might seek in God, short of oblivion (if you’re into that sort of comfort), is moot. God is capable of the smallest betrayals and his miracles are scant. He is “a shivering / God robed in rats who refuses / to learn your name” (“But The Dead Do Not Know Anything”). At the same time, poems like “Every Concept Is In Itself An Exaggeration” blend philosophy and absurdity with soul and skill, and lines like, “Feathers and fathers are right when they say Your fat is always in the way” made me laugh out loud, as did later lines from the same poem:

When you cry you are a lawn flamingo

When God cries he’s a velvet painting of God

Privitello ends “Every Concept, etc.” with the line “All of our feelings are kitsch,” but it’s one of a handful that don’t ring true for me—this book is not kitsch, and neither are the feelings it aims to describe, which read more like visions than emotions. On rare occasions, she leans toward this self-referential cleverness—poems like the Artaud-inspired “Drainage For Angels” are weakened a bit by lines like “Cum is the base word of cumulus,” which seem like they are there for the sake of their in-jokiness, doing nothing to further the poem’s brutal obsessions. They threaten to demean the consciousness at work in these poems, which is invested in exposing the matter at hand—it’s big and smart with no need to let you know how big and smart it is. That, after all, is God’s job—he “…designs / girls and doesn’t call them the next day.”

But it’s only a line. “Drainage For Angels” also reveals Privitello’s ability to be contemporary, a poet using form to criticize the culture she finds herself dropped into and living. It ends,

If a doe-eyed angel reaches out his hand it is not a valentine

He is asking to autopsy you with his fingernails

Whether or not this is the first time you feel pleasure from violence

Or the first time you let your mouth admit it

Your body will be yeasted, trespassed, flame-fucked, rising

These angels are a reclamation, the terrifying seraphim of the Hebrew Bible, murderous with greed—a hard no to the sanitized American Christianity that has commodified them. Like everything in this book, they translate a sense of the dire: it’s the end of the world. Some readers might find this dramatic, but we are living a dramatic moment, one this book names rather than circumvents. As a Plath scholar, maybe I just like my poems high-stakes; maybe that’s why I like this book so much. Whatever the reason, when, toward its end, I read the lines, “I have a story about madness that starts with God and ends / with God” (“The Rules Of Madness”), I believed them. I flipped back to the first page and started again.