The Twoness of Truth: A Review of Ananda Lima’s Amblyopia

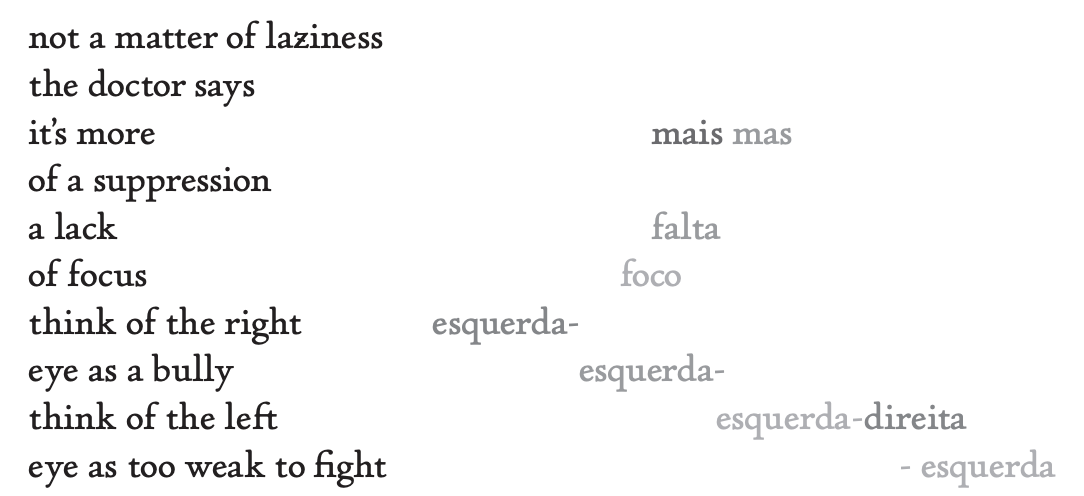

In Amblyopia, Ananda Lima interrogates the imprecision of sight, the movement from one language to another, the blurred space in between. The opening poem, “Amblyopia” begins with the speaker’s diagnosis. Lima uses the formal constraints of margins and white space to enact the twoness of the speaker’s eyes: the left column of text is in English, left margin-aligned, while the Portuguese text of the right column wavers across white space, fading between shades of grey.

How do we recognize truth? Is it with our eyes?

It is difficult to discuss sight in poetry without discussing the image. After two “Amblyopia” poems, Lima invokes Oppen, the objectivist, through two poems titled “Dark Room,” which bookend the rest of the collection (again, a twoness). Oppen was after an empirical truth; he wanted to show the object as the thing itself, sans our messy, human commentary which blurred the object’s view. For Oppen, the image was the truth.

What is an image? Maybe a kind of pictorial representation in language, or better yet, a moment of lyric suspension containing narrative details that evoke movement through time. But an image is something we perceive with our physical eyes or the mind’s eye. Lima’s speaker turns against the objectivity implicit within Oppen’s world view. Both of Lima’s “Dark Room” poems complicate Oppen’s “A Theological Definition.” Oppen’s poem begins, “A small room, the varnished floor / making an L around the bed,” whereas Lima’s “Dark Room” begins:

A small room

vanishes

In Lima’s world, the image is a subjective source of truth, open to interpretation. “In Zoológico, Circa 1982” the speaker begins a memory recall, and quickly admits “…I don’t know if what I recall is that day a blend of different days or a photograph. I remember the sky burned white behind us in a picture but I also see it big and bright blue…” (9). Memory is conflated with image. The mind’s eye sees a combination of something remembered, something manufactured, something invented.

No element of perception is spared by our thoughtful, inquisitive speaker. Language too, and the meaning of words, is called into question again and again. In “I As Letter in Bottle” the speaker shows her son “how the ls can look like is” and later:

again I go I tell him that i can

sound like I like ih but I can’t hold on

to the dam walls the blurring barriers

between these four is clear and still like glass

to him little American he is

to me orange raging flood I travel

Note the shift contained within the sonnet’s final couplet, the stark contrast between how the son sees the world, versus how the speaker does.

To see the world through another’s eyes is not just an intellectual or aesthetic experience, but a muscular one. Throughout the collection, the formal inventiveness of these poems embodies this muscularity. In “Hart Chart,” the poem takes on the form of a Hart Chart, moving the reader’s eyes through a visual test, commanding the reader to: “P U T A N E Y E T O R E S T” (7).

Oppen’s “A Theological Definition” ends with an image, a vision of “Windows opening on the sea, / The green painted railings of the balcony /Against the rock, the bushes and the sea running.” But the speaker has already disproved the objectivity of images. And yet, this is a book of poems. The reader must use the mind’s eye to see. Can the speaker show the reader something that contains a kind of truth? The answer, of course, is to forgo the world of sight. The speaker turns inward, away from any universal claims, moving closer toward the inner life:

the word

for developing a photograph

in Portuguese is revelação

revelation

I lie

down,

take the room in

close

my eyes.